Marriage, Mayhem, & Presidential Politocs:

The Robards-Jackson Backcountry Scandal

http://frank.mtsu.edu/~lnelson/Toplovich04.htm

Also See Editorial newspaper The Tennessean

Ann Toplovich

Tennessee Historical Society

Since 1860, the biographies of Andrew Jackson have paid great attention to the impact of Rachel Donelson’s 1793 divorce from Lewis Robards on the 1828 presidential campaign. Although research over the past thirty years has raised doubts about the Jackson party’s account of the divorce, little attention has been paid to the Robards side of the story beyond its later use by the Adamsites. This paper presents an updated look into the Robards-Donelson marriage, the Jackson elopement, and how spin, even in the 1820s, could make presidents bigger than life and men like Robards almost disappear from history.

Marriage and Elopement

In the fall of 1780, John Donelson took his extended family and thirty slaves from the beleaguered Cumberland Settlements to the slightly more secure Davies Station near Crab Orchard, Kentucky. [1] The move ended a journey that had begun a year earlier, when Donelson sold his plantation and iron foundry in backcountry Virginia, carried his family into upper East Tennessee, led an adventurous voyage down the Tennessee and up the Cumberland River, and set up what proved to be a temporary camp near the future Nashville. Donelson was a robust man in his fifties, a surveyor and former member of the House of Burgesses, an Indian negotiator for Virginia, and an agent of Richard Henderson. Pittsylvania County historian Larry Aaron places the value of Donelson’s sale of land and foundry in Virginia at nearly $1,000,000 in today’s dollars, and Donelson was also rich in family. [2] He and his wife Rachel Stockley had eleven children, all of whom moved west with him. His youngest daughter and tenth child, Rachel, was thirteen when the Donelsons arrived in Kentucky. She was an automatic member of the backcountry elite and a family with extensive political and land speculation connections.

Crab Orchard lay at the juncture of the Wilderness Road and the Cumberland Trace, placing the Donelsons on the main route for travelers between Virginia and Harrodsburg and between the Nashville settlements and Kentucky. Through most of the 1780s, settlers still lived “forted up” together as protection from Indian attacks, and the settlers at Crab Orchard would encounter most of the new people moving into the region. In early 1784 one such family came down the Wilderness Road on their way to Harrodsburg, the Robardses of Goochland County, Virginia.

The family was led by Lewis Robards, born in 1758 among the large plantations between the Tidewater and the Piedmont. He was the seventh child of planter William Robards, Sr., (1733-1783) but the first child of William’s second wife, Elizabeth Woodson Lewis (1735-1805). Seven more children would be born in later years, giving Lewis thirteen full and half-siblings in all, including eight brothers. The Welsh Robardses immigrated to Virginia in 1710. Elizabeth Lewis’s family lines were all prominent in the founding of the Virginia Colony. Lewis was born into a kin network of the Virginia planter elite that was even more influential than Rachel Donelson’s. [3]

Besides his planter interests, William Robards was a militia lieutenant during the French and Indian War and a member of the Goochland County Committee of Safety in 1775. When the American Revolution began, the five Robards boys of age followed his example by serving in the Virginia Regiment Continental Line, most rising to the officer ranks. Lewis enlisted as a private in 1778 and by January 1781 was a captain. That year he fought at the burning of Richmond, skirmished near the James River, and was at the siege of Yorktown. By the end of 1781, Captain Robards was blooded by four years of service. [4]

Like many veterans of the day, Lewis now looked west for his fortune. Robards and his brothers George, Jesse, and Joseph spent much of 1782 and 1783 “in the wilderness [of the Kentucky district] clearing their land for cultivation, and helping rid the land of Indians.” [5] The main plantation was located on 400 acres on Cane Run in the future Mercer County. Because of the threat of Indian attack, the Robards boys lived at Fort Harrod, a few miles from the homestead.

William Robards planned to move his second family to Cane Run in late 1783 and divided his Goochland County land among the children of his first wife. However, William died unexpectedly that November, leaving his wife Elizabeth a life interest in the 400 acres. He divided his 29 slaves and 2 mulatto indentured servants among his wife and her children, as well as leaving her boys almost 11,000 acres in Kentucky. Lewis Robards received two slaves and over 1,800 acres. In early 1784, Lewis and his younger siblings, some married, moved with his widowed mother and the slaves to Mercer County, living first at Harrodsburg and then their complex of log buildings on Cane Run. [6]

It is likely that Lewis Robards met Rachel while traveling to Virginia through Crab Orchard, perhaps as early as 1782. Another possibility is that Rachel visited the Cane Run neighborhood in 1784, when a Presbyterian meeting house opened there. A Robards family tradition holds that John Donelson’s wife Rachel lived for a time with her younger children in one of the Robards’s log houses, throwing the younger Rachel and Lewis together. [7]

The courtship accelerated when John Donelson decided to move his family back to the Cumberland Settlements in 1785. Rachel was 18; her career as a frontier belle took place in Kentucky, and she may have been reluctant to leave her friends. 27 year old Captain Robards had the wealth and large, influential kin network in Kentucky and Virginia to match that of the Donelsons. The arrangement was advantageous to both families, and in February 1785 John Donelson registered his permission for Rachel to marry Robards. On March 1, the couple married at Harrodsburg. [8]

They lived with the Widow Robards, along with several other Robards siblings and their young children, boarders, and a large slave community. Rachel’s own family moved to Nashville that summer; in the fall John Donelson was killed. [9] The newlywed Rachel became fully dependent on her new family for support.

In the early months of the marriage, Lewis flourished in Mercer County. In 1786 he was a captain of militia and may have been a merchant. [10] The number of petitions on debt filed in court by Lewis support merchant dealings. But the cases against Lewis for debt suggest that he was having money troubles. [11] Lewis’s father had selected his younger brother George as executor of his will, which hints at an unstable financial personality. Arguments over his father’s estate and land holdings ultimately estranged Lewis from George – George’s wife Elizabeth Sampson would support some of the more damning stories about Lewis in the Nashville Committee affidavits of 1827 – that he was violently jealous and that he frequented the slave quarters at night. [12]

Meanwhile, Rachel may have had difficulty adjusting to her new life. Bassett wrote that the young Rachel “is described as a woman of a lively disposition, by which is meant that she was not that obedient, demure, and silent wife which some husbands of the day thought desirable.” [13] A woman who is not obedient and demure doesn’t fare well with a jealous husband.

In 1787, Peyton Short became a boarder at the Robards’s place about the same time as fellow Virginian James Overton. Short was a William and Mary graduate, heir to a plantation fortune, and his brother William was secretary to Thomas Jefferson, then ambassador to France. [14] James’s brother John would write:

“I had not lived [at Harrodsburg] many weeks before I understood that Captain Robards and his wife lived very unhappily, on account of his being jealous of Mr. Short. My brother [James], who was a boarder, informed me that great uneasiness had existed in the family for some time before my arrival.... The uneasiness between Captain Robards and lady continued to increase, and with it great distress of the mother, and considerably with the family generally; until early in the year 1788 ... I understood from the old lady, and perhaps others of the family, that her son Lewis had written to Mrs. Robards’ mother, the widow Donelson, requesting that she would take her home, as he did not intend to live with her any longer.” [15]

There was something to Robards’s suspicions. Short later confessed to his friend Henry Banks that he had great “sympathy” for Rachel and determined to marry her after her separation from Robards. He planned on converting his inheritance into money or slaves “and if Mrs. Robards would accept him as a husband[,] to go with her to the Spanish Dominions on the Mississippi; and there to settle himself for life.” [16] As fate would have it, Robards intercepted the letter from Short that held this offer and pursued Short to Virginia. In Richmond, Short offered Robards either the satisfaction of a duel or a pay off with money. Robards settled for $1,000. [17]

In late summer 1788, Rachel’s brother Samuel came for her and they traveled to Nashville. [18] Robards family accounts say Rachel had simply gone on a visit to her family. [19] Jackson accounts claim that Robards had thrown her out -- John Overton states that he affected a reconciliation between Lewis and Rachel after Overton moved to Nashville in February 1789 and boarded with the Donelsons. [19] However, in July 1788, Robards had bought almost 1,700 acres in the Cumberland, including a 640 acre plantation near Widow Donelson. [20] This supports the position that Robards intended to settle permanently in the area with Rachel and that they had not separated when she came south later that summer. The couple was already together at the Widow Donelson’s before Overton came to Nashville.

One thing is certain: when Overton arrived, Andrew Jackson was also boarding there. [21] At the time, Jackson was a 21 year old attorney for the State of North Carolina and had only tenuous connections to a few North Carolina politicians and speculators, including Richard Henderson’s brother Tom and his law teacher Spruce McKay. His parents were Ulster Scot immigrants to the Waxhaws of Carolina; his father was a subsistence farmer who died worn out from work before Jackson’s birth, and by the end of the Revolutionary War he had lost both his mother and his brothers. By the standards of the planter elite, Jackson was a virtual nobody, but he very much wanted to be a somebody. By the summer of 1789, Rachel’s friendship with Jackson caused such gossip that Short heard Rachel was involved with him and he married another woman. [22] That same summer witnesses saw stormy arguments between Robards and Rachel as well as altercations between Robards and Jackson – in a blackberry patch, in an orchard. [23]

That summer, Jackson also traveled to Natchez, where he took the oath of allegiance to the king of Spain on July 15. [24] The oath was not needed to trade there, which Jackson was doing, but it did confer citizenship rights and the promise of land grants. Jackson’s action begs the question of when his plans for an elopement with the married Rachel began.

The events that followed the summer of 1789 have been covered with the accretions of the Jackson spin machine of the 1820s. The accepted tale is still that Robards left for Kentucky, vowing never to see Rachel again. The innocent and wronged Rachel went to Natchez in a large party that happened to include Andrew Jackson. Jackson, back in Nashville, heard in 1791 that Robards had obtained a divorce, and hurried immediately to Natchez to marry Rachel. The Jacksons then returned to Nashville as an accepted couple. [25] However, in the 1970s, Robert Remini did a masterful job of piecing the actual story together, showing that the Nashville Committee’s dates were all moved a year later in time to cover the Jacksons’ tracks in regard to Robards’s divorce action. [26] Moreover, no credible evidence of a marriage ceremony in Natchez has ever been found.

However, the Jackson elopement occurred even earlier than Remini assumes. The couple returned with a group from Natchez in the summer of 1790, not in Remini’s March 1791 nor the Nashville Committee’s fall 1791. Hugh McGary, a Mercer County military leader, was among the travelers and he gave Robards the eyewitness he needed to Jackson and Rachel’s “bedding together.” Mercer County records show that McGary could only have been traveling with them in July 1790 – the date given in the fall 1790 divorce petition charging Rachel’s act of adultery. [27]

Divorce in the EAR

The crux of the attacks in the 1824 and 1828 presidential campaigns was whether Rachel Robards had been deserted by her husband or whether she deserted him. Remini, and Andrew Burstein following Remini, concludes that Jackson carried off Rachel in December 1789 in order to provoke a divorce. [28] However, this presumes that the provocative grounds and the way to get a divorce were understood in 1789. Given Rachel’s compromised reputation from her friendships with male boarders and the young age of the lovers (only 22), the elopement was most likely a matter of passion, although they also may have been seeking an extralegal solution. If capable of calculation (and Jackson certainly was), they also realized that the vivacious Rachel shed herself of a problem husband and the orphaned Jackson gained an heiress and an influential kin network.

We must digress here for a little background on marriage and divorce in the 1700s and the affect of the American Revolution on American practices. [29] Until 1753, English law recognized marriages that couple had made with no ceremony or even no witnesses. Yet at the same time, divorce was barely tolerated – between 1670 and 1857, Parliament granted only 325 full divorces, and only four of those went to women. Divorce from bed and board was a little easier to get – the couple was legally separated, the woman received financial support to live elsewhere, but neither spouse could remarry. The process for a complete divorce called for three steps: 1) one filed suit for damages against the wife’s lover in civil court; 2) this was followed by a suit for separation in an ecclesiastical court; and 3) the divorce action was completed by Parliament, if success was found in the prior two suits. [30] (Divorce was seen – and still is -- primarily as a tort, seeking recompense for a willful injury.)

Legal marriage with its formal contracts regarding assets was mostly the purview of the landed, moneyed, and/or titled classes – for them the transfer of wealth and bloodlines required strict control from one generation to the next. However, the difficulties of dissolving marriage could combine with older folk ways to create a variety of extralegal solutions for infelicitous unions. For centuries, some among the lower classes of Great Britain had formed unions, dissolved them, and formed new marriages – all that mattered was whether the couples involved and the community they lived in accepted the actions. For these groups, marriage was often ended by desertion by one spouse, with both then free to “wed” another. Bride-stealing and wife-selling were other methods of shedding – or acquiring – a spouse. [31] Women were as active in deserting spouses as men.

These customs arrived with British settlers in the American colonies of the seventeenth century, and they flourished most in the backcountry – even in such Puritan strongholds as Massachusetts. Through the late 1600s and early 1700s, religious and political authorities sought to rein in the sexuality of the colonists, mostly succeeding in recognition of only legal unions and forbidding dissolution of marriage in only the most egregious of circumstances. However, self-determination in marriage, and the ending thereof, was especially pernicious the western borderlands of the South well into the mid and late-1700s. Visitors to the backcountry of the Carolinas, including the Waxhaws, especially condemned these practices. John Urmstone was “shocked to discover migrants abandoned legal spouses and then entered adulterous relationships or bigamous marriages when settled in Carolina.” [32] Charles Woodmason also noted that “colonists formed and dissolved cohabitational relationships without observing martial formalities.” [33] However, as long as the community accepted their unions, backcountry folk cared little for these condemnations from Anglican ministers.

By the births of Robards, Donelson, and Jackson in the Southern backcountry, these folk ways were being swiftly supplanted by legal marriages, as more people of means entered the territory and, more importantly, as local magistrates became easily available to issue marriage bonds. By the 1780s, the American Revolution resulted in other factors affecting marriage and divorce: among these were the concept that an individual had as much right to overthrow an intolerable social contract as did a colony a king and that the states could now create their own statutes regulating sexual unions. A ferment of radical social theory regarding the rights of individuals rammed into the new republic’s desire to mold a pious, ethical, and patriotic populace.

The new states began to address the riddle of divorce in the 1780s, just as Rachel Donelson was marrying Lewis Robards. Their attempt to end their marriage would fall into an even more tumultuous time. The Robardses may be condoned for the actions they took due to the confusion of the day, but Jackson, as an attorney surrounded by lawyer friends, likely had a better understanding of the illegal nature of his actions.

The formation and ending of unions outside of law continued to be a significant concern to the governments of Virginia and North Carolina, which had jurisdiction over the Kentucky and Mero districts where the Robardses and Jackson lived. (Other states were also struggling with these issues.) As early as 1778, the North Carolina state assembly passed a law regulating the “rites of matrimony” in an attempt to curtail extralegal, self-declared unions. [34] Divorce was extremely rare; petitions were heard by the state assemblies, with no authority yet given to the courts unless the assembly so directed. In a further effort to regulate irregular unions, in 1788, the year North Carolina attorney Andrew Jackson met Rachel Robards, the state assembly resolved that legislation was needed “to punish bigamy and polygamy.” [35] Spruce McCay, Jackson’s legal mentor, recorded the conviction of a man in his community of bigamy that year, but he questioned whether the crime was “punishable in this state.” [36] A law was subsequently passed in 1790, the year the Jacksons returned to Nashville as a couple, “to restrain all married persons from marrying again whilst their former wives or former husbands are living” and denouncing the “many evil-disposed persons going from one part of our country to another, and into places where they are not known” to enter bigamous marriages knowing full well that their legal spouses were alive. [37]

Was Jackson aware of these moves on the part of North Carolina? In addition to McCay, Jackson had three friends closer to home who could have informed him of the new measures against bigamy. Donelson family friend James Robertson served in the North Carolina assembly through 1789. [38] More extraordinary is that Rachel’s brother, Stockley Donelson, and her brother-in-law Robert Hays represented Tennessee counties in that body from 1787-1789 and were present at the legislation’s debates. [39] Rachel was living with Jane Donelson and Robert Hays at the time of her elopement with Jackson [40] – can we believe that the issue of bigamy was not broached? Conveniently, North Carolina had ceded Tennessee to the Congress in late 1789 and the Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio was established in May 1790. What conclusion may we draw from Andrew and Rachel fleeing to Spanish Natchez in December 1789 – before news had reached Nashville of North Carolina’s cession of Tennessee – and their return in June 1790, just weeks after Nashville entered federal control? Whereas North Carolina would not legally recognize their illegal and felonious union – a crucial key to Rachel inheriting slaves and money from her father’s estate – the nation’s Congress had not yet taken up matters of marital reform. [41]

Meanwhile, what was the status of divorce in the Kentucky District, where lived Rachel’s husband Lewis Robards? In 1785, the couple had legally married in Mercer County, then part of Virginia. Virginia followed the English parliamentary model of hearing divorce petitions in the legislative body and making decisions on an ad hoc basis – without consideration of application on a wider basis. Between 1786 and 1827, when the statutes were changed, the Virginia assembly received 268 petitions for divorce, and only granted forty-two bills of divorce – a little more than 15%. [42]

Robards and his wife parted in Nashville in the fall of 1789 and by December, Rachel was on her way to Natchez with Jackson. Lewis Robards’s response to his wife’s elopement is somewhat puzzling, if one buys the Jackson accounts – he took no action other than petitioning for divorce, hardly the violent outburst one would expect from a jealous spouse. Robards family accounts insist that Rachel was “stolen from her husband’s hearth” by Jackson, and one Robards descendant relates a tale of Robards physically pursuing Jackson as he carried off Rachel. [43]

As mentioned earlier, Robards found his eyewitness to Rachel’s adultery in July 1790. That fall, Robards’s brother-in-law, Jack Jouett, a member of the Virginia assembly from the Kentucky District, sponsored Robards’s petition for divorce. [44] (Only one petition before Robards’s had found success, that of Anne Dantignac in 1789. [45]) A bill was passed in December 1790 that would allow Robards to sue for divorce in the Kentucky District court: “A jury shall be summoned who shall... find for the plaintiff or in case of inquiry into the truth of the allegations contained in the declaration, shall find substance, that the defendant hath deserted the plaintiff, and that she hath lived in adultery with another man since that desertion, the said verdict shall be recorded, and, thereupon, the marriage between the said Lewis Robards and Rachael Robards shall be totally dissolved.” [46]

Robards would not move toward the jury trial until 1792, providing fodder for the Jackson claim that Rachel and Andrew thought that a divorce had taken place and were surprised to learn otherwise. (Of course, this ignores the fact that they had eloped a year before the Virginia bill was passed.) However, yet another jurisdiction obstacle was being created – by the Kentucky statehood conventions. Ten conventions took place in nearby Danville between 1784 and 1792 as Kentucky sought independence from Virginia; statehood loomed in 1785, then again in 1787 and 1789, and was finally achieved in June 1792. [47] Delays in the Robards divorce proceedings were inevitable as jurisdiction bounced back and forth.

Despite the ongoing divorce action, Robards still saw himself as having rights over Rachel’s property, and indeed the Virginia law of coverture gave him such rights. In January 1791, he wrote her brother-in-law Robert Hays saying Robards would depend on Hays and John Overton to make sure no advantage was made in his absence from Nashville where his rights to John Donelson’s estate were concerned. [48] Nevertheless, when the estate was divided in April 1791, the woman termed “Rachel Jackson” received two slaves, livestock, a bed, and “35 hard dollars.” [49] In the divorce statute passed in Tennessee in 1799, a divorced spouse could not marry their partner in adultery and “a divorced woman who openly cohabitated with her lover was declared incapable to dispose of her real estate whether during her life or by a will.” [50] The Jacksons had caught another legal break.

Having lost out on Rachel’s inheritance, Robards placed the required notices of divorce action in the Kentucky Gazette of February and March, 1792, summoning Rachel Robards to court “to answer a charge of adultery exhibited against her.” [51] She did not choose to attend the trial, which took place in August and September 1793. That Robards actually won a divorce may be due to having U.S. Senator John Brown for his lawyer and Kentucky hero Hugh McGary as his witness. [52] Twelve jurors found “the Defendant Rachel Robards hath deserted the Plaintiff, Lewis Robards and hath and doth Still live in adultery with another man. It is therefore considered by the Court that the Marriage between the Plaintiff and the Defendant be desolved” as of September 27. [53]

Clearly, how to pursue a divorce was a confusing prospect in the early American republic, especially in a borderland where territorial standing and statehood were under negotiation. So why would Robards pursue a divorce? Why not enter into a new extralegal union of his own? And why would Rachel Donelson and Andrew Jackson return from Natchez to Nashville? For Robards, honor was the issue. For Donelson and Jackson, it was community acceptance.

For a man, especially a Southern man living in a hierarchical slave-owning society, a deserting wife represented a loss of control over his family and thus a loss of honor and status in that society. Thomas Buckley, in The Great Catastrophe of my Life: Divorce in the Old Dominion, presents persuasive evidence that for a male plaintiff, the public nature of seeking a legal divorce allowed the community to discuss the separation and maintain or restore the petitioner’s social status regardless of the assembly’s action. [54] The community’s judgement was given higher place than individual autonomy, and the legislative process in and of itself could be seen as terminating the marriage, even if the petition was denied in Richmond. Part of this was achieved by the number of signatures from the community that would be attached in support of petitions – sometimes seventy or eighty. [55] Robards seems to have recognized that the community had set him free before the Kentucky courts did – Robards quietly married Hannah Winn in Jefferson County in December 1792, while his divorce was still in process in Mercer County. [56] They would remarry legally in Mercer in November 1793. [57] Robards and his second wife had ten children; he died in 1814 after an uneventful life post-Rachel Donelson.

The divorce and trial were undoubtedly the talk of Kentucky – news and gossip traveled fast where marital scandal was involved. [58] (The Robards family was still talking about it over a hundred years later. [59]) Here enters Henry Clay. In late 1797, Joseph Robards traveled home from Virginia with a young lawyer, who spent several days at the Widow Robards. That young lawyer was Clay, just coming out to Kentucky. [60] One has to wonder – did Joseph gossip about Andrew Jackson stealing his brother’s wife? Did Lewis himself tell his story to Clay? Was this the true root of the scandal exhumed in the later presidential elections?

A woman, however, did not have recourse to the divorce process as a means of recovering honor. If her petition failed, her husband would still control her life because of coverture – a wife had no legal entity separate from her husband. And if she won, there were still losses to a woman’s character – marriage to a man to whom she had been linked before the divorce was seen as a confession of illicit sex. [61] That a woman of Rachel Donelson’s status chose the extralegal recourse of desertion to end her marriage is extraordinary. Elite women were expected to tolerate outrageous behavior on the part of their husbands, seeking separation only when violent behavior placed their lives in danger. [62] Moreover, in the early republic, women embodied the ideals of decorum, self-control, and sexual virtue and should hold their sexually self-indulgent mates in check. [63] Any woman who sought comfort from the sufferings of her marriage in a relationship with another man was viewed with contempt. [64] The issue was so morally weighted that in 1796 the General Conference of Methodists instructed ministers “not to receive any person into society who had put away a wife or husband and married again, no matter what the crime that caused them to part.” [65] Other denominations too often preached about the subject from the pulpit and at camp meetings.

Although the Donelson family and members of their sphere of influence embraced the extralegal union of Rachel and Andrew Jackson – a marriage that became legal in January 1794 – there is clear evidence that members of the wider Tennessee community saw Rachel as a fallen woman and Jackson as a rake for many years afterward. As Jackson rose in prominence, the history of the marriage impacted their public reputations. John Sevier’s contempt of Jackson as a seducer was central to the duel correspondence of 1803, and Rachel’s virtu, or lack thereof, was a subtext of the Charles Dickinson duel of 1806 and perhaps the Benton shootout of 1813. It could not have surprised the Jacksons that Rachel’s divorce and remarriage would become a flashpoint when Jackson sought the presidency.

Campaigns of 1824 and 1828

John Quincy Adams’s campaigns would attack Jackson on many fronts, making his passion – his lack of self-control – central to their argument that he would devastate the integrity of the republic and its institutions. Jackson’s elopement with the married Rachel Robards was a perfect example of this rampagious personality and the nature of marriage became a wedge issue for the elections of 1824 and 1828. The campaigns – and the public – entered into debate on marital fidelity as a symbol of national unity, adultery as political chaos, and whether private acts should be drawn into the public arena. [66]

In the 1824 election, Rachel’s divorce was used mostly in a whispering campaign; most references show up in private correspondence rather than in editorials or political broadsides. Jackson and his supporters attempted to spin the tale by placing all blame on Lewis Robards and in one narrative of the first marriage make Rachel the agent seeking the divorce. Pro-Jackson congressmen shared the campaign’s talking points with influential persons. Eleanor Custis Lewis, active in Washington’s “parlor politics,” wrote to a friend in February 1824 that Congressman George Tucker has given her the true story, exonerating the Jacksons:

“I am happy to assure you my Friend that Gen’l Jackson is not the wretch he is represented. [Cong] Tucker has conversed with several persons of great respectability & well acquainted with every circumstance, within the last week. He left us this morning, & this is declared to be the real state of the case. Miss Donaldson ran away with, and married, her first husband at 14 years old. Genl J had lived a long time with her Parents & was under obligations to them. He did not see the Daughter for two years after her marriage during which time she endured the most cruel treatment from her husband, he frequently beat her severely, forced her to fly for refuge to a neighbours house. She was persuaded to return several times & was obliged to leave him as often, at last Gen’l J happen’d to witness this conduct & was called on, as her Parents friend, for protection. He interfered, & threaten’d to chastise the husband if he was ever guilty again. He still persisted, & she was obliged to sue for a divorce. A considerable time elapsed after this before she married Gen’l Jackson. Her first Husband was never a soldier under J – & has been dead many years. Mr T adds that the circumstances and the case gained Jackson the esteem & approbation of the whole neighborhood in which they occur’d. Col Gadsden [??] always speaks of Mrs J as an excellent woman & he is devoted to Gen’l Jackson. [Sen. Robert] Hayne assured me that no man was ever more vilely calumniated than Jackson – & these are most honorable & very correct evidences....” [67]

The Jackson spin was not enough to offset the John Quincy Adams-Henry Clay alliance, and Adams won the presidency through Congress’s vote in early 1825. Robert Remini observes the scandal held “enough ammunition to kill a regiment of presidential candidates.” [68]

The 1828 presidential campaigns would be different in that the Jacksonians would undertake a more organized and legalistic defense of Rachel’s divorce and remarriage – this time with Rachel in a passive role – while the Adamsites would come out with guns blazing in print. On March 23, 1827, the first salvos were fired by Charles Hammond in the Cincinnati Gazette; Henry Clay was implicated in giving Hammond the facts of the Robards divorce. Until Jackson, Hammond thundered, the nation had been a place:

“where no man can succeed to a place of high trust who does not respect female virtue: or who stands condemned as the seducer of other men’s wives, and the destroyer of female character...[should we] give sanction to conduct, which is calculated to unhinge the fundamental principles of society?....Let all inducements to the maintenance of conjugal fidelity be broken down: let all veneration for the marriage state and covenant be destroyed; and let me then ask, what there is in social life worthy of regard?....Show to the world your abhorrence of a man, who disregards the laws which even savages revere.”

The Robards case was “an affair in which the National character, the National interest, and the National morals, were all deeply involved...a proper subject of public investigation and exposure.” [69] Was Rachel suitable to be “at the head of female society in the United States?” No “intelligence mind [can] doubt that Mrs. Jackson was unfaithful to her marriage vow with Robards...[or] believe that she would have been guilty of the great indiscretion of flying beyond the reach of he husband, with a man charged to be her paramour, were she innocent of the charge” upheld in the divorce suit. Jackson was at fault; a caring husband “would never consent that the wife of his bosom should be exposed to the ribald taunts, and dark surmises of the profligate, or to the cold civility or just remark of the wise and good.” Instead of running for president, he should have shielded the “bruised and broken flower.” [70]

The charges were taken up by many other papers in the country. Among them, an 1828 issue of the Massachusetts Journal editorialized that if Jackson, “the Great Western Bluebeard,” persists in placing his wife “among modest women, he shall meet a firmer resistance before he fights her and his own way into the presidential mansion....Who is there in all this land that has a wife, a sister or daughter that could be pleased to see Mrs. Jackson (Mrs. Roberts [Robards] that was) presiding in the drawing-room at Washington. THERE IS POLLUTION IN THE TOUCH, THERE IS PERDITION IN THE EXAMPLE OF A PROFLIGATE WOMAN And shall we standing in a watch-tower to warn our countrymen of approaching danger seal our lips in silence, in respect to this personage and HER PARAMOUR, great and powerful as he is and captivating as he renders himself with his ‘bandanna handkerchief,’ ‘his frock coat,’ his amiable condescensions, and the fascinations of his BAR-ROOM and PUBLIC TABLE TALK.” [71]

Jackson partisans parried the attacks as best they could, given that all the legal documents showed Rachel had been found an adulteress by a jury. In 1827, the key piece of Jackson’s defense was published, A Letter from the Jackson Committee of Nashville, in Answer to One from a Similar Committee, at Cincinnati, upon the Subject of Gen. Jackson’s Marriage, by the “Nashville Committee” that was created in 1826 to build a plausible argument. Affadavits such as that from Mary Bowen were quoted: “Not the least censure ought to be thrown upon any person but Mr. Robards....This was the language of all the country, and I never heard until now that there was any person living who had entertained a different opinion, except Mr. Robards himself, in whose weak and childish disposition, I think the whole affair originated.” [72]

Among the other counterattacks from the Jackson camp was the 1828 Vindication of the Character and Public Services of Andrew Jackson in Reply to the Richmond Address, signed by Chapman Johnson, and to other electioneering calumnies. The tract tried to castigate Adams for harming a defenseless woman as well as the Jacksons’ sensibilities. The assaults on Rachel were an assault on Andrew Jackson, wounding him twice for her sake and for his honor. The Adamsite charges invaded “the inmost recesses of his family, the honor of his wife....and his domestic peace...to serve the purposes and prop up a falling party...no man has been more foully slandered.” [73] Jackson partisans hoped to flip the charges against Jackson of wife stealing to charges against Adams for wife slandering. (However, since the author of the tract was Henry Lee, notorious in Virginia for his own adultery with his wife’s sister, one has to wonder how much vindication the tract could deliver. [74])

The Adams campaign presented marriage as a social contract that extended beyond individuals into the national polity, and argued for strict government control over domestic relations. They took a cue from the evangelical movement of the Second Great Awakening, which found lack of sexual self-discipline morally repellent and wanted a firm delineation of the unbreakable boundaries of marriage. In this trope, Adams was portrayed as a responsible, self-restrained Christian gentleman and women were called upon to actively defend their chastity. [75]

The Jacksonians meanwhile presented marriage as a private and romantic arrangement, where chivalry and heartfelt sentiment should have sway over overly-restrictive legal forms. The choices of private individuals were weighed against rigid moral prescription, and political secularism was preferred – marriage should be a matter of individual choice and local concern. The ideal Jackson man was brave, chivalrous, and self-sufficient, and his masculine strength would shield weak women, who were never seen as active enough to be the deserter from a marriage, but rather were the deserted. Jackson and his friends went to great lengths to mold the Robards divorce narrative in such a way that Rachel was left by Lewis, and so stranded, had no choice but to turn to Jackson for protection. [76]

These partisan views were so different in their competing narratives of the Robards affair – challenging beliefs on manhood and womanhood, passion and restraint, divorce and remarriage – that they inevitably contributed to the emergence of a two-party system in the United States. Jackson prevailed in the election of 1828, and the Whig Party was born in reaction to his autonomous style of government.

Conclusion

From the founding of the American republic, the new states wrestled with their citizens’ desires to be freed from failed marriages. For political philosophers such as Thomas Paine, as a people could break the social contract with an oppressive government, so should an individual be able to break a marriage contract with an oppressive spouse. Yet others saw marital virtue as the glue that held the republic together, and any movement toward sexual permissiveness was a step toward anarchy. In the late 1700s, most state legislatures tried to thrash out these issues by debating divorce petitions, like that of Lewis Robards, but many Americans in the backcountry still took matters in their own hands through extralegal means, as did Rachel Donelson and Andrew Jackson. By the 1820s, most state assemblies passed laws delineating strict grounds for divorce and turned over decisions to the judiciary, although the debate still burned.

The presidential campaigns of the 1820s had no choice but to address the narrative of Rachel Donelson’s divorce. Although divorce scandals fascinated the public, the Adamsites may have pressed too hard in their attacks, ultimately making the Jacksons into sympathetic figures. (The wronged husband, Lewis Robards, was long dead and could not make his own case.) In the face of the hard legal evidence that Andrew Jackson had eloped with Rachel while she was still very much married and that they had indeed lived in adultery, the Jackson partisans prevailed with their position that marriage should be “romantic and private with a distinct preference for heartfelt sentiments over precise legal forms.” [77]

Although Rachel Donelson and Andrew Jackson did in truth flaunt the moral and legal codes of their times, today they are legendary lovers. If Andrew Jackson is admired for anything, even by his most determined critics, it is for his devoted marriage to Rachel and his vigorous defense of her reputation. She is now a stick figure in the story, a passive belle tossed away by one man and swept up by another. Lewis Robards is hardly more than a name, although in 1790 he was the frontier nabob and Jackson little more than a knave. By an effective campaign strategy, the “American Jezebel” and the “Great Western Bluebeard” have come down to us as the most romantic pair in presidential history.

http://frank.mtsu.edu/~lnelson/Toplovich04.htm

[1]. Donelson placed claims on about 2,300 acres on Cedar Creek near Davies Station, and he may have established a home there. Willard Rouse Jillson, Old Kentucky Entries and Deeds (Baltimore, 1999) [pgs]. See also Charles Monty Pope, “John Donelson, Pioneer” (masters thesis, University of Tennessee, 1969), 35.

[2]. Larry G. Aaron to Ann Toplovich, 2 September 2004.

[3]. See Ann Toplovich, “The Life and Marriages of Lewis Robards,” paper presented at Kentucky-Tennessee American Studies Association Annual Meeting, 19 March, 2004.

[4]. James Harvey Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family (Franklin, Ind., 1910), 26.

[5]. Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 53.

[6]. Will of William Robards, reproduced in Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 133-136.

[7]. Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 54.

[8]. (DS, Stanford, Lincoln County, Ky., Office of the County Court Clerk, in Sam B. Smith, ed., The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol I, 1770-1803 (Knoxville, 1980), 423.

[9]. Pope, “John Donelson, Pioneer,” 48-49.

[10]. Michael L. Cook, compiler, Mercer County Kentucky Records, Vol 1 (Evansville, 1987), 8, and George M. Chinn, The History of Harrodsburg and the Great Settlement...1774-1900 (city, year), 76.

[11]. See Cook, Mercer County Kentucky Records, 16, 23, 31, 34, 47, 62, 77.

[12].(John Downing to J. H. Eaton, December 20, 1826, Jacob McGavock Dickinson Papers, Tennessee Historical Society Collections, Tennessee State Library and Archives, as quoted in Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767-1821 (New York, 1977), 44.

[13]. John Spencer Bassett, The Life of Andrew Jackson (New York, 1916), 16.

[14]. William Barlow and David O. Powell, “Heroic Medicine in Kentucky in 1825: Dr. John F. Henry’s Care of Peyton Short,” Filson Club Historical Quarterly (April, 1989):244-245 n.3.

[15]. John Overton, Nashville Committee report, as reproduced in James Parton, Life of Andrew Jackson, Vol.1 (New York: Mason Brothers, 1861), 148.

[16]. Henry Banks to John Overton, 4 June 1827, as quoted in Marquis James, The Life of Andrew Jackson (New York, 1940), 854-856 n.64.

[17].Henry Banks to John Overton, 10 May 1827, as quoted in Marquis James, The Life of Andrew Jackson (New York, 1940), 854-856 n.64. The letters from Henry Banks to John Overton are now among the Nashville Committee correspondence, Jacob McGavock Dickinson Papers, Tennessee Historical Society collections, TSLA.

[18]. Mary French Caldwell, General Jackson’s Lady (Nashville, 1936), 110.

19. A. Wright affidavit, 27 May 1827, Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington, as reproduced in Mary Powell, Hammersmith, Hugh McGary, Sr., Pioneer of Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana (Wheaton, Ill, 2000), 170-171; see alsoRobards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 55.

[19]. Overton, Nashville Committee report, as reproduced in Parton, 149.

[20]. Smith, ed., Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol 1, 84.

[21]. Overton, Nashville Committee report, as reproduced in Parton, 149.

[22]. Henry Banks to John Overton, 4 June 1827; Barlow and Powell, “Heroic Medicine in Kentucky in 1825,” 244-245 n.3.

[23]. For blackberry patch incident, see Parton, Life of Andrew Jackson Vol. 1, 168-169, and for orchard incident see John Overton report as quoted in Parton, 149.

[24]. See Robert V. Remini,”Andrew Jackson Takes an Oath of Allegiance to Spain” (Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Spring 1995): 2-15.

[25]. Overton, as quoted in Parton, 148-153.

[26]. See the chapter “Marriage,” in Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 57-69.

[27]. McGary was a member of the Mercer County Court; court records show his only trip to Natchez in this period was in the spring and early summer of 1790. See Mary Powell Hammersmith, Hugh McGary, Sr., Pioneer of Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana (Wheaton, Ill., 2000), 164, 171.

[28]. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 65, and Andrew Burstein, The Passions of Andrew Jackson (New York, 2003), 245.

[29]. Among the secondary sources used for information on views on divorce in the EAR include Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the Election of 1828,” The Journal of American History (December 1993), Basch, Framing American Divorce: From the Revolutionary Generation to the Victorians (Berkeley, 1999), Buckley’s The Great Catastrophe of my Life: Divorce in the Old Dominion (Chapel Hill, 2002), Godbeer’s Sexual Revolution in Early America (Baltimore, 2002), Goodhart et al, “An Act for the Relief of Females: Divorce and the Changing Legal Status of Women in Tennessee, 1796-1860, Part I,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Fall 1985), and Sachs, “The Myth of the Abandoned Wife: Married Women’s Agency and the Legal Narrative of Gender in Eighteenth-Century Kentucky,” Ohio Valley History (Winter 2003).

[30]. Basch, Framing American Divorce, 23-34.

[31]. For discussions of wife-stealing as a backcountry custom, see David Hackett Fisher, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York, 1989), 669-671. For wife-selling, see Basch, Framing American Divorce, 38.

[32]. As quoted in Godbeer, Sexual Revolution on Early America, 119.

[34]. Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America, 149.

[36]. Spruce McKay Notebook, Records of the Trials in Morgan District, 1786-1795, as quoted in Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America,149.

[37]. Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America, 149.

[38]. “James Robertson” in Robert M. McBride and Dan M. Robison, Biographical Directory of the General Assembly, Vo. 1, 1796-1861 (Nashville, 1975), 629.

[39]. “Stockley Donelson,” ibid, 207; “Robert Hays,” ibid, 349.

[40]. Overton, as quoted in Parton, 148-153.

[41]. The North Carolina assembly would hear only fifteen petitions for divorce between 1779 and 1800 and only one was granted. The first divorce statute for that state, placing divorce before the courts, was passed in 1814.

[42]. Buckley, The Great Catastrophe of My Life, 24.

[43]. Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 58; see also H. D. Pittman, The Belle of the Blue Grass Country (Boston, 1906).

[44]. Captain John “Jack” Jouett was a well-known hero of the American Revolution in Virginia, who married Sarah “Sally” Robards in August 1784. Jouett was a delegate to the Virginia legislature in 1787 and 1790 and represented Mercer County in the Kentucky legislature in 1792 and Woodford County in 1795-1797. See Lewis Collins, Historical Sketches of Kentucky (Maysville. Ky., 1847).

[45]. Buckley, The Great Catastrophe of My Life,17-18.

[46]. Virginia Acts, 1790, Ch. XCII, as reproduced in Smith, The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol. 1, 424.

[47]. William Green, “Statehood Conventions,” in John K. Kleber, ed., The Kentucky Encyclopedia (Lexington, 1992), 848-849.

[48]. Lewis Robards to Robert Hays, 9 January 1791, as reproduced in Smith, ed., The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol. 1, 424-425.

[49]. Davidson County Wills and Inventories, 1,.96-201; ordered recorded, Davidson County Court Minute Book, 1783-1809, p. 424, as reproduced in Smith, ed., The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Vol. I, 425-427.

[50]. Lawrence B. Goodheart, Neil Hanks, and Elizabeth Johnson, “‘An Act for the Relief of Females...’: Divorce and the Changing Legal Status of Women in Tennessee, 1796-1860, Part I,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Fall 1985): 321.

[51]. Kentucky Gazette, 4,11,18, 25 February, and 3,10,17, 24 March1792.

[52]. For a brief biography of John Brown, see “John Brown,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, http://bioguide.congress.gov. For a brief biography of Hugh McGary, see “Hugh McGary” in Kleber, ed., The Kentucky Encyclopedia, 597

[53]. Kentucky State Archives, Court of Quarter Sessions Book, 1792-96, p. 105.

[54]. Buckley, The Great Catastrophe of My Life, 24.

[55]. Basch, Framing American Divorce, 39.

[56]. Jefferson County Virginia-Kentucky Early Marriages, Book 1, 1781-July 1826 (Louisville, 1980), 17.

[57]. Marriage Bonds and Consents, 1786-1810, Mercer County Kentucky (Harrodsburg, 1970), 95.

[58]. For a discussion of the public’s fascination with divorce, see Basch, Framing American Divorce, 149.

[59]. This is best evidenced by the inclusion of the Robards view of the Jackson elopement in Robards family members’ obituaries; for example, see Lewis Robards, Jr., obituary in the 27 January 1891 Louisville Courier-Journal and William Johnston Robards obituary in the February 1905 Louisville Herald.

[60]. As stated in the December 1858 Louisville Courier obituary for Joseph Robards, reprinted in Robards, History and Genealogy of the Robards Family, 88.

[61]. Basch, Framing American Divorce, 178.

[62]. Buckley, The Great Catastrophe of My Life, 56.

[63]. Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America, 196.

[64]. For discussion on early republic views of women’s role as keepers of virtue, see Basch and Godbeer.

[65]. Godbeer, Sexual Revolution in Early America, 149.

[66]. Basch’s article on the 1828 campaign analyses these issues very well and is an important source for this section.

[67]. Patricia Brady, ed., George Washington’s Beautiful Nelly: The Letters of Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, 1794-1851 (145-146.

[68]. Robert Remini, The Election of Andrew Jackson (Philadelphia, 1963), 152.

[69]. We the People, April 12, 1828, as quoted in Basch. “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the 1828 Election,” 901.

[70]. Charles Hammond, View of General Jackson’s Domestic Relations, as quoted in Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the 1828 Election, 905.

[71]. Political Extracts from the Leading Adams Papers, the Massachusetts Journal (Boston, 1828) as quoted in Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the 1828 Election,” 905.

[72]. Letter from the Jackson Committee of Nashville, in Answer to One from a Similar Committee, at Cincinnati, upon the Subject of Gen. Jackson’s Marriage (Nashville, 1827), 14-17.

[73]. Vindication of the Character and Public Services of Andrew Jackson in Reply to the Richmond Address, signed by Chapman Johnson, and to other electioneering calumnies (Boston, 1828), as quoted in Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the 1828 Election,” 899.

[74]. For an assessment of Henry Lee scandal, see Buckley, The Great Catastrophe of My Life, 114-116. Lee and his wife lived at the Fountain of Health resort near the Jacksons in the late 1820s and Henry Lee briefly worked as Jackson’s biographer.

[75]. Basch, “Marriage, Morals, and Politics in the 1828 Election,” 896.

[77]. Basch, “Marriage,” 894.

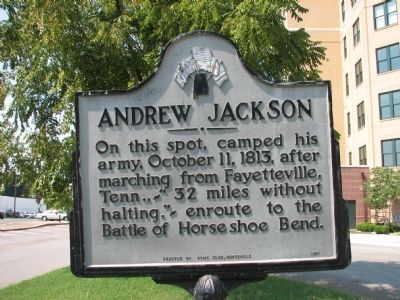

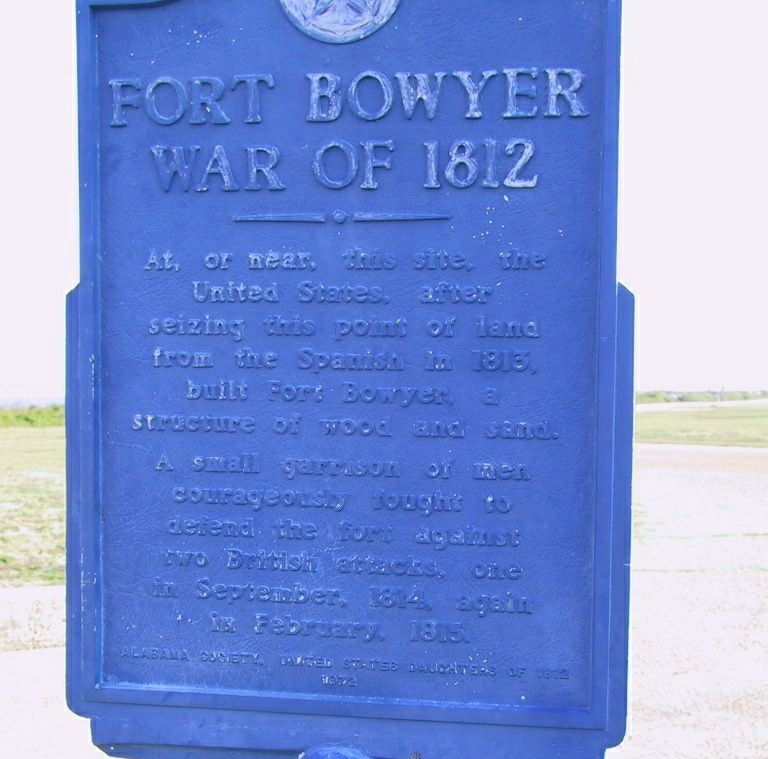

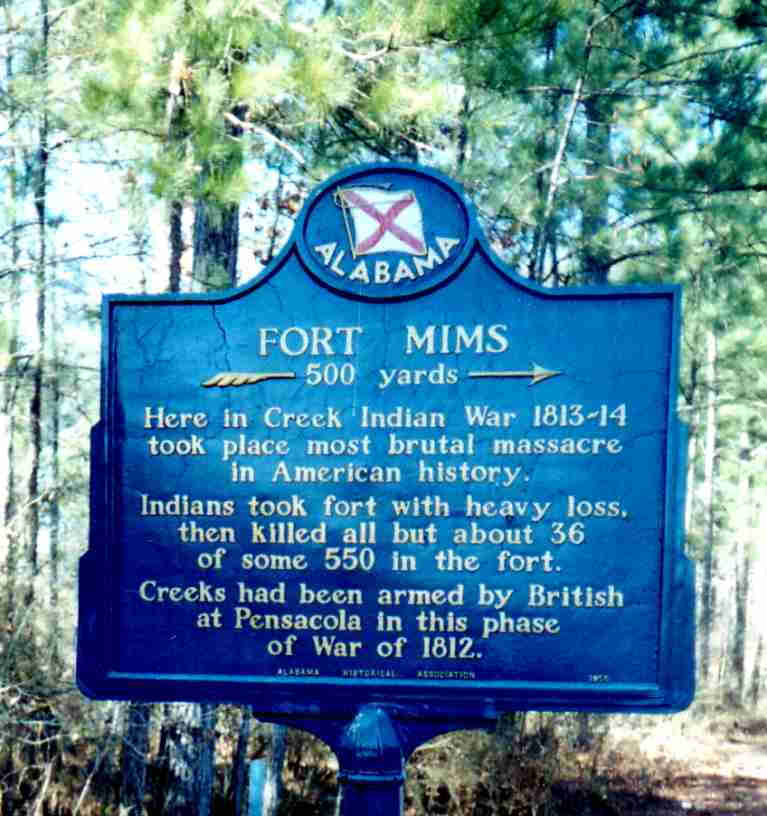

1813 .. 1814

Creek Indian War, a part

of the War of 1812, fought largely within the boundaries of present-day

Alabama. Andrew Jackson of Tennessee became a military hero as a consequence

of his campaigns fought in Alabama culminating in the Battle of New Orleans

January 08, 1815

July 27, 1813: Battle of Burnt Corn Creek

August 30, 1813: Fort Mims Massacre

See Web Site Dedicated to Fort Mims Massacre Created by the Fort Mims Restoration Association LINK

See 2009 Photo Display

*The actual number of those who died at Fort Mims was much less than the 500 that were reported in later accounts.

.

November 3, 1813: Battle of Tallushatchee

November 9, 1813: Battle of Talladega

November 12, 1813: The Canoe Fight

November 18, 1813: Hillabee Massacre

November 29, 1813: Battle of Autosse

December 23, 1813: Battle of Holy Ground (Econochaca)

January 22, 1814: Battle of Emuckfau Creek

A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF BURNT CORN

From the letter of General James Wilkinson, we learn that more than three hundred hostile Creeks, under the Prophet Francis, were camped, on the 25th of June, at the Holy Ground. General Wilkinson writes: "The last information received of their doings was on Wednesday [the 23d of June], by Ward's wife, who has been forced from him with her children. She reported that the party, thus encamped, were about to move down the river to break up the half-breed settlements, and those of the citizens in the fork of the rivers." While this was, no doubt, the real and ultimate design of the hostile Creeks, it was first necessary to put themselves on a thorough war footing by procuring supplies of arms and ammunition from Pensacola.

With this object in view, at some period in the early part of July, a party of Creeks, comprising a portion, if not all, of the hostile camp at the Holy Ground, with many pack-horses, took up the line of march for Pensacola. This party was under the command of Peter McQueen, at the head of the Tallassee warriors, with Jim Boy, as principal war chief, commanding the Atossees,* and Josiah Francis, commanding the Alibamos. Pickett gives the entire force as amounting to three hundred and fifty warriors; Colonel Carson, in a letter to General Claiborne, estimates them at three hundred; but General Woodward, in his Reminiscences, simply states that their numbers have been greatly overrated. "On their way," writes Pickett, "they beat and drove off every Indian that would not take the war-talk. "On their arrival at Burnt Corn Spring, situated at the crossing of the Federal and the Pensacola roads, they burned the house and corn crib of James Cornells, seized his wife and carried her with them to Pensacola, where she was sold to Madame Baronne, a French lady, for a blanket. A man, named Marlowe, living with Cornells, was also carried prisoner to Pensacola. Cornells, it seems, was absent from home, at the time of this outrage. We hear of him, soon afterwards, at Jackson, on the Tombigbee, "mounted on a fast-flying grey horse," bringing to the settlers the tidings of Creek hostilities.

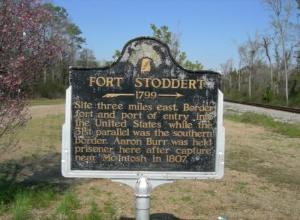

* Pickett in his narrative has here evidently made a slip writing Autaugas for Atossees. H. S. H. The perilous condition of the southern frontier at this period, the early part of July, is well portrayed in the following passages from Pickett: "The inhabitants of the Tombigbee and the Tensaw had constantly petitioned the Governor for an army to repel the Creeks, whose attacks they hourly expected. But General Flournoy, who had succeeded Wilkinson in command, refused to send away of the regular or volunteer troops. The British fleet was seen off the coast, from which supplies, arms, ammunition, and Indian emissaries, were sent to Pensacola and other Spanish ports in Florida. Everything foreboded the extermination of the Americans in Alabama, who were the most isolated and defenceless people imaginable." When Colonel Joseph Carson, commanding at Fort Stoddart, was informed that the above mentioned force of Creek warriors had gone to Pensacola, he despatched David Tate and William Pierce to the town to ascertain the intentions of the Creeks and whether Governor Manique would grant them a supply of ammunition. The information gained by these spies and reported on their respective returns, all summed up, was that the Creeks, on their arrival in Pensacola, had called upon the Governor and presented him a letter from a British general in Canada. This letter had been given to Little Warrior when he was in Canada and at his death was saved by his nephew and afterwards given to Josiah Francis, The Creeks, whether right or wrong, supposed that this letter requested or authorized the Governor to supply them with ammunition. The Governor, in reply, assured them that it was merely a letter of recommendation, and at first refused to comply with their demands. He, however, appointed another meeting for them, and the Creeks, in the meanwhile, made every exertion to procure powder and lead by private purchase. According to Tate's information, which he received from some of the prisoners whom the Creeks had brought down with them, their language breathed out vengeance against the white people and they dropped some hints of attacking the Tensaw settlers on their return. The Creeks finally succeeded in their negotiation with the Governor, who issued an order supplying them with three hundred pounds of powder and a proportionate quantity of lead. To obtain this large supply, McQueen handed the Governor a list of the towns ready to take up arms, making four thousand eight hundred warriors. Even this large amount of ammunition was not satisfactory to the Creeks; they demanded more, but it seems that Manique yielded no further to their demands. The Creeks now openly declared that they were going to war against the Americans; that on their return to the nation they would be joined by seven hundred warriors at the Whet Stone Hill,* where they would distribute their ammunition and then return against the Tombigbee settlers. They now held their war-dance, an action equivalent to a formal declaration of war.

* The hill on which the present town of Lownsoro is situated. Such was the information brought by the spies from Pensacola, and their evidence clearly shows that the disaffected section of the Creek Confederacy was now committed to open war against the Americans. No other construction can be placed upon the words and actions of the agents or representatives of this disaffected section,--the hostile party in Pensacola. We may conjecture that this party left Pensacola about the twenty-fourth of July, but, as will be noticed hereafter, it seems that it was only a part of the force, mainly under the command of Jim Boy that took up the line of march, while the greater party, from some cause, tarried a while longer in Pensacola. A slight incident here, perhaps, is worthy of being placed on record to the credit of Jim Boy. While in Pensacola the Creeks met with Zachariah McGirth a man well known in the Creek nation. Some of the Creeks wished to kill him. But Jim Boy interposed and said that the man or men that harmed McGirth should be put to death In the meanwhile, the inhabitants of the Tombigbee and the Tensaw were in a state of great alarm. Many had abandoned their farms and taken refuge in the forts situated along the Tombigbee and the Alabama. Judge Toulmin, writing from Fort Stoddart, the twenty-third of July, says, "The people have been fleeing all night." This brief sentence clearly reveals the alarm and anxiety pervading the Alabama frontier at this period. Upon the report of the spies from Pensacola relative to the action of Governor Manique and the Creeks, Colonel James Caller, of Washington County, the senior militia officer on the frontier, forthwith ordered out the militia. A force was soon embodied and enrolled under his command. Colonel Caller resolved to intercept the Creeks on their return and capture their ammunition. His command, at first, consisted of three small companies, two from St. Stephens, commanded respectively by Captains Baily Heard and Benjamin Smoot, and one company from Washington County, commanded by Captain David Cartwright. With this force Colonel Caller crossed the Tombigbee at St. Stephens, Sunday, July 25th; thence passing through the town of Jackson, he marched to Fort Glass, where he made a short halt. At this place he was reinforced by accompany under Captain Sam Dale, with Lieutenant Walter G. Creagh as second in command. Another force had also joined him in the expedition commanded by William McGrew, Robert Callier, and William Bradberry. The whole party were well mounted and carried their own rifles and shot guns, of every size and description. Captain Dale carried a double barrel shot gun--an unusual weapon in that day. An eye-witness has described Colonel Caller at Fort Glass as wearing a calico hunting shirt, a high bell-crowned hat and top boots and riding a large fine bay horse. Leaving Fort Glass, the party bivouacked the ensuing night at Sizemore's ferry, on the west bank of the Alabama River. The next morning they crossed the river, the horses swimming by the side of the canoes. This occupied several hours. They now marched in a southeastern direction to the cowpens of David Tate, where a halt was made. Here Colonel Caller received another reinforcement, a company from Tensaw and Little River, commanded by the brave half-breed, Captain Dixon Bailey. The whole force, composed of white men, half-breeds and friendly Indians, now numbered one hundred and eighty men, rank and file, in six small companies. From the cow-pens they marched to the intersection of the Wolf-trail and the Pensacola road, at or near the site of the present village of Belleville, in Conecuh County, where they camped for the night. The next morning, the twenty seventh of July the command was reorganized. William McGrew was chosen Lieutenant Colonel, and Zachariah Phillips, McFarlan, Wood, and Jourdan were elected to the rank of Major. It is stated that this unusual number of field officers was made to satisfy military aspirations. The command now took up the line of march down the Pensacola road, which here ran, and still runs, parallel with Burnt Corn Creek. About eleven o'clock the spies returned at a rapid rate and reported that they had found the enemy encamped near Burnt Corn Creek, a few miles in their advance, and that they were busily engaged in cooking and eating. A consultation of the officers immediately took place, and it was decided to take the Creeks by surprise. The troops were thrown into three divisions, Captain Smoot in front of the right, Captain Bailey in front of the centre, and Captain Dale in front of the left.

As the descriptions of the Burnt Corn battle ground given by Meek and Pickett are somewhat vague and inaccurate, a more correct account of the topography, gained from personal observation, is here given to the reader. Burnt Corn Creek, near which the battle was fought, runs southward for several hundred yards, then making an abrupt bend, runs southeastward for half a mile or more. Right at the elbow of the bend is the crossing of the old Pensacola road. The low pine barren enclosed in this bend--not a peninsula as called by Pickett--is enveloped by a semicircular range of hills, which extends from the creek bank on the south some half a mile below the crossing, and terminates on the west at the bank, some three hundred yards above the crossing. This western terminus is now locally known as the Bluff Landing. The Pensacola road from the crossing runs northward some two hundred yards, then turning runs eastward half a mile, making a continuous and gradual ascent up the slope of the hills, and then again turns northward. The spring, now known as Cooper's Spring, is situated about half a mile nearly east of the crossing, and about one hundred and fifty yards south of the road. It gushes forth at the base of a steep hill and is the fountain head of a small reed-brake branch, which empties into the creek about two hundred yards below the crossing. The hill, at the base of which the spring is situated, is about the centre of the semicircular range of hills which envelops the pine barren.

About sixty yards northwest of the spring, between the spring and the road, is a comparatively level spot of land, about an acre in extent. This spot, we conjecture, was the Creek camp, or at least where the main body was encamped, as it is the only place immediately near the spring suitable for a camp. The hill here rises steep and abruptly to the northeast, and a hostile force could well approach and charge down this hill within close gunshot of the camp before being seen. This locality famed as the battle ground of Burnt Corn is in Escambia County, one-half a mile from the line of Conecuh County, on the north. As reported by the scouts, the Creek camp was near the spring, and their pack-horses were grazing around them. No rumor of the foe's advance had reached their ears; all were careless, off their guard and enjoying themselves, for good cheer was in the Muscogee camp. Their martial spirits, as we may well imagine, were not now stirred by thoughts of war and bloodshed, but were concentrated on the more peaceful delights of cooking and feasting, the pleasures of the pot, the kettle, and the bowl. The Burnt Corn battlefield was in the unorganized part of Mississippi Territory (in the Indian country proper) in the year 1818. Monroe county organized in 1815, included Burnt Corn. In 1818 the same locality was in Conecuh county established that year. Now it seems, it is in Escambia county, established in 1868 although Brewer, writing in 1872 still places the battle ground of Burnt Corn in Conecuh. (The following cut will give some idea of the locality).

Colonel Callers troops, as we may conjecture, must have turned to the left, off the road, perhaps near the Red Hollow, about a mile distant from the spring, and thence approached the Creek camp from the northeast and east, as from the nature of the country this was the only route they could have taken so as to surprise the Red Stick camp.* The troops moved cautiously and silently onward until they reached the rear of the hill that overlooked the Creek camp. Here, Pickett says, they dismounted; but Meek says the main body dismounted; yet neither Pickett nor Meek makes any statement as to the disposition of their horses--whether they were tied or were consigned to the care of a guard, or whether each trooper, as he dismounted, left his horse to shift for himself. From the fact that many of the horses fell into the hands of the enemy, one is led to the conjecture that no regular system was employed, but that every man did that which was right in his own eyes. After dismounting, the troops moved silently to the crest of the hill, whence they made a rapid charge down its slope and opened fire upon the Creek camp, as the red warriors stood, sat, or reclined in scattered groups over the ground. The Creeks, though startled by this sudden and unexpected onset, quickly sprang to arms, returned the fire, and for several minutes bravely withstood the charge of the whites, then gave way and retreated in wild confusion to the creek. Early in the fight a Creek woman and a negro man were slain. It is stated that the latter, who was busily engaged in cooking, had ample time to make his escape, but being a slave and non-combatant he doubtless apprehended no danger from the whites. A portion of the troops pursued the Indians to the creek--Meek says they even drove them across the creek into a reed-brake beyond--but we think this latter statement exceedingly doubtful.

While these were performing this soldierly duty, the more numerous party devoted their energies to capturing and leading off the pack-horses. This led to a disastrous reverse. The Creeks in the cane and reed-brakes soon saw the demoralization of the greater part of the whites and the fewness of the assailants confronting them. They rallied, and, with guns, tomahawks and war clubs, rushed forth from the swamp, and with the fiercest cries of vengeance charged upon their foes and drove them headlong before them. Colonel Caller acted bravely, but unable to restore order, he commanded the troops to fall back to the hill so as to secure a stronger position and there to renew the battle. The plundering party, misconstruing this order, and seeing the fighting portion of the troops falling back before the enemy, were now seized with a panic, and fled in wild confusion, still, however, notwithstanding their terror, driving their horses before them, some even mounting their prizes so as to more quickly escape from the fatal field. In vain did Colonel Caller, Captain Bailey and other officers endeavor to rally them and persuade them to make a stand against the foe. Terror and avarice proved more potent than pride and patriotism, and the panic-stricken throng surged to the rear. Only about eighty fighting men now remained, and these had taken a stand in the open woods at the foot of the hill. Commanded by Captains Dale, Bailey, and Smoot, they fought with laudable courage for an hour or more under the fire poured upon them by McQueen's warriors from the cover of the thick and sheltering reeds. The battle may now be briefly described as "a series of charges and retreats, irregular skirmishes and frequent close and violent encounters of individuals and scattered squads." It was noticed that the Creek marksmanship was inferior to that of the Americans. It was in the fight at the foot of the hill that Captain Dale was wounded by a rifle ball, which struck him in the left side, glanced around and lodged near the back bone. The captain continued to fight as long as his strength permitted, and then threw aside his double barrel into the top of a fallen tree. This gun, we may here state, Dale recovered after the war from an Indian, at Fort Barancas. About the same time that Dale was wounded, Elijah Glass, a twin brother of David Glass, was slain. He was standing behind another soldier, who was in a stooping position, when a rifle ball struck him fatally in the upper part of the breast.

* The hostile Creeks were often called Red Sticks because their war-clubs were invariably painted red. "Red Stick" was considered an honorable appellation, and as such it will occasionally be used in this work. "Red Stick War" is the name by which the War of 1813 is still known among the Creeks of the Indian Territory. H. S. H. The battle now at last began to bear hard upon the Americans. Two-thirds of the command were in full retreat, and no alternative lay before the fighting portion but to abandon the field, which they did in the greatest disorder. Many of them had lost their horses, some of which had been appropriated by the fugitives, and others, in some manner, had fallen into the hands of the enemy, among these, the horses belonging to Colonel Caller and Major Wood. The troops now fled in all directions. Some succeeded in reaching and mounting their own horses; others mounted the first horses they came to; in some cases, in their eagerness to escape, two mounting the same horse; while others actually ran off afoot. It was a disgraceful rout. "After all these had left the field," writes Pickett, "three young men were found, still fighting by themselves on one side of the peninsula, [bend,] and keeping at bay some savages who were concealed in the cane. They were Lieutenant Patrick May, a private named Ambrose Miles, and Lieutenant Girard W. Creagh. A warrior presented his tall form. May and the savage discharged their guns at each other. The Indian fell dead in the cane; his fire, however, had shattered the Lieutenant's piece near the lock. Resolving, also to retreat, these intrepid men made a rapid rush for their horses, when Creagh, brought to the ground by the effects of a wound which he received in the hip, cried out "Save me, Lieutenant, or I am gone". May instantly raised him up, bore him off on his back, and placed him in the saddle, while Miles held the bridle reins. A rapid retreat saved their lives. Reaching the top of the hill, they saw Lieutenant Bradberry, bleeding with his wounds, and endeavoring to rally some of his men." This was the last effort made to stem the tide of disaster.

Two young men were slain in the battle, _____ Ballard and Elijah Glass, both it is believed, being members of Dale's company. Ballard had fought with great bravery. Just before the final retreat, he was wounded in the hip. He was able to walk, but not fast enough to reach his horse, which in the meantime, had been appropriated by one of the fugitives. A few of the soldiers returned and successively made efforts to mount Ballard behind them on their horses, but the Indians pressed them so closely that this could not be done. Ballard told them to leave him to his fate and not to risk their own lives in attempting to save him. At last the Indians reached him, and for some moments, he held them at bay, fighting desperately with the butt of his musket, but he was soon overpowered and slain. Several Indians now sprang forward, scalped him and began to beat him with their war clubs. Two of the retreating soldiers, David Glass and Lenoir, saw this. Glass was afoot, Lenoir mounted. "Is your gun loaded," asked Glass of Lenoir. "Yes," was the reply. "Then shoot those Indians that are beating that man yonder." Lenoir hesitating, Glass quickly spoke, "Then lend me your gun." Exchanging guns, Glass then advanced a few paces and fired at two or three of the Indians whose heads happened to be in a line, and at the discharge one of them fell, as Glass supposed, slain or wounded. This was the last shot fired in the battle of Burnt Corn, which had lasted from about midday until about three o'clock in the afternoon. The Creeks pursued the whites nearly a mile in the open woods and nothing but their inability to overtake them saved the fugitives from a general slaughter. Pickett writes: "The retreat continued all night in the most irregular manner, and the trail was lined from one end to the other with small squads, and sometimes one man by himself. The wounded travelled slowly, and often stopped to rest." Such was the result of the battle of Burnt Corn, the first engagement in the long and bloody Creek War. Most of the Creek pack-horses, about two hundred pounds of powder and some lead was all the success the Americans could claim from this engagement. Their loss was two men killed, Ballard and Glass. Fifteen were wounded, Captain Sam. Dale, Lieutenant G. W. Creagh, Lieutenant William Bradberry, shot in the calf of the leg; Armstrong, wounded in the thigh; Jack Henry, wounded in the knee; Robert Lewis, Alexander Hollinger, William Baldwin, and seven others whose names have not been preserved.

The Creek loss is not positively known. Colonel Carson, in a letter to General Claiborne, written a few days after the battle, states that from the best information it was ten or twelve killed and eight or nine wounded. As to the numbers engaged at Burnt Corn, we know that the American force numbered one hundred and eighty. General Woodward, in his Reminiscences, states, on the authority of Jim Boy, that the Creek force was two-thirds less. He writes. "Jim Boy said that the war had not fairly broke out, and that they never thought of being attacked; that he did not start [from Pensacola] with a hundred men, and all of those he did start with were not in the fight. I have heard Jim tell it often that if the whites had not stopped to gather up the pack horses, and had pursued the Indians a little further, they, the Indians, would have quit and gone off. But the Indians discovered the very great confusion the whites were in searching for plunder, and they fired a few guns from the creek swamp, and a general stampede was the result. McGirth always corroborated Jim Boy's statement as to the number of Indians in the Burnt Corn battle." The above, perhaps, may be regarded, in some measure, as the Creek version of Burnt Corn. If possession of the battlefield may be considered a claim to victory, then Burnt Corn may well be regarded a Creek victory. After the battle, a part of the Red Sticks retraced their steps to Pensacola for more military supplies, and a part returned to the nation. Their antagonists, Colonel Caller's troopers, were never reorganized after the battle. They returned home, in scattered bands, by various routes, and each man mustered himself out of service. About seventy of them on the retreat collected together at Sizemore's Ferry, where, for a while, they had much difficulty in making their horses swim the river. David Glass finally plunged into the stream and managed to turn the horses' heads towards the other shore. After the horses had all landed on the further bank, the men crossed over in canoes.

Colonel Caller and Major Wood, as we have related, both lost their horses at Burnt Corn. As the fugitives shifted, every man for himself, these two officers were left in the rear. They soon became bewildered and lost their way in the forest, and as they did not return with the other soldiers, their friends became very apprehensive as to their safety. "When General Claiborne arrived in the country, he wrote to Bailey, Tate, and Moniac, urging them to hunt for these unfortunate men. They were afterwards found, starved almost to death, and bereft of their senses." When found, Colonel Caller had on nothing but his shirt and drawers. After the war, the Colonel, with some difficulty, recovered his fine horse from the Creeks. But Major Wood was not so fortunate.

Colonel J. F. H. Claiborne, in his "Life of Sam Dale," writes: "Colonel Caller was long a conspicuous man in the politics of Mississippi Territory, often representing Washington County in the legislature. No one who knew Caller and Wood intimately doubted their courage; but the disaster of Burnt Corn brought down on them much scurrility. Major Wood, who was as sensitive as brave, bad not the fortitude to despise the scorn of the world, and sought forgetfulness, as too many men often do, in habitual intemperance."